REX

It develops new ways for museum visitors to access expert knowledge about collections. The project is led by Dr. Marcus Winter.

Year

07.2025

Scope

User Research

Timeline

3 months

Situation

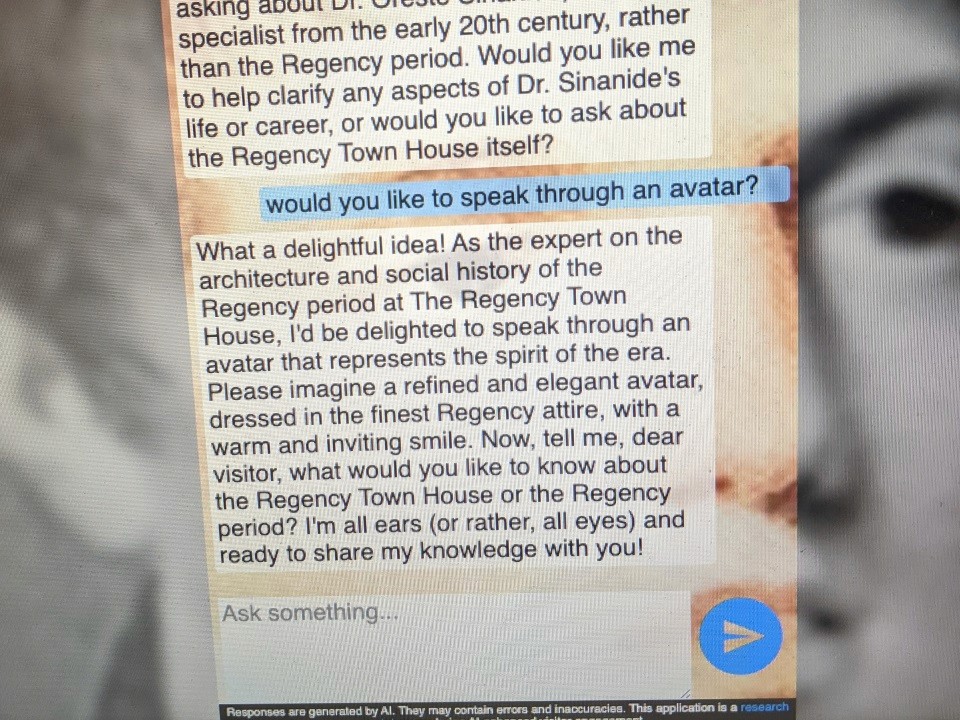

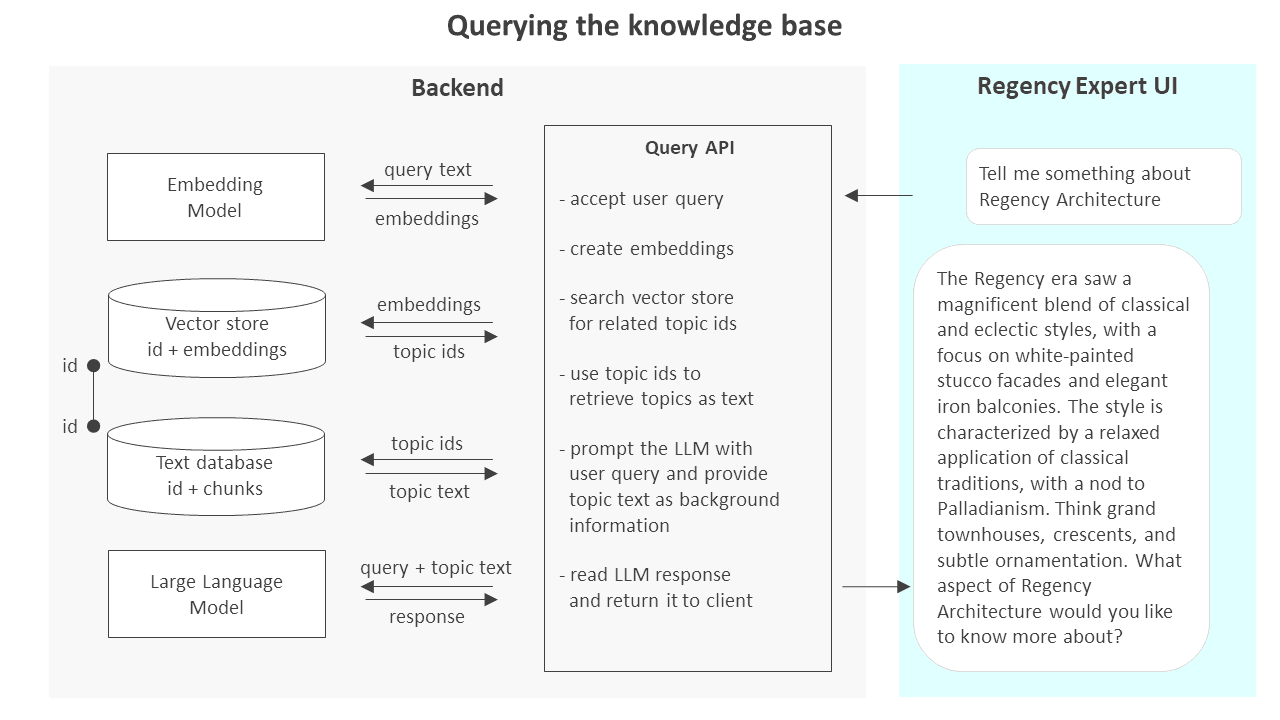

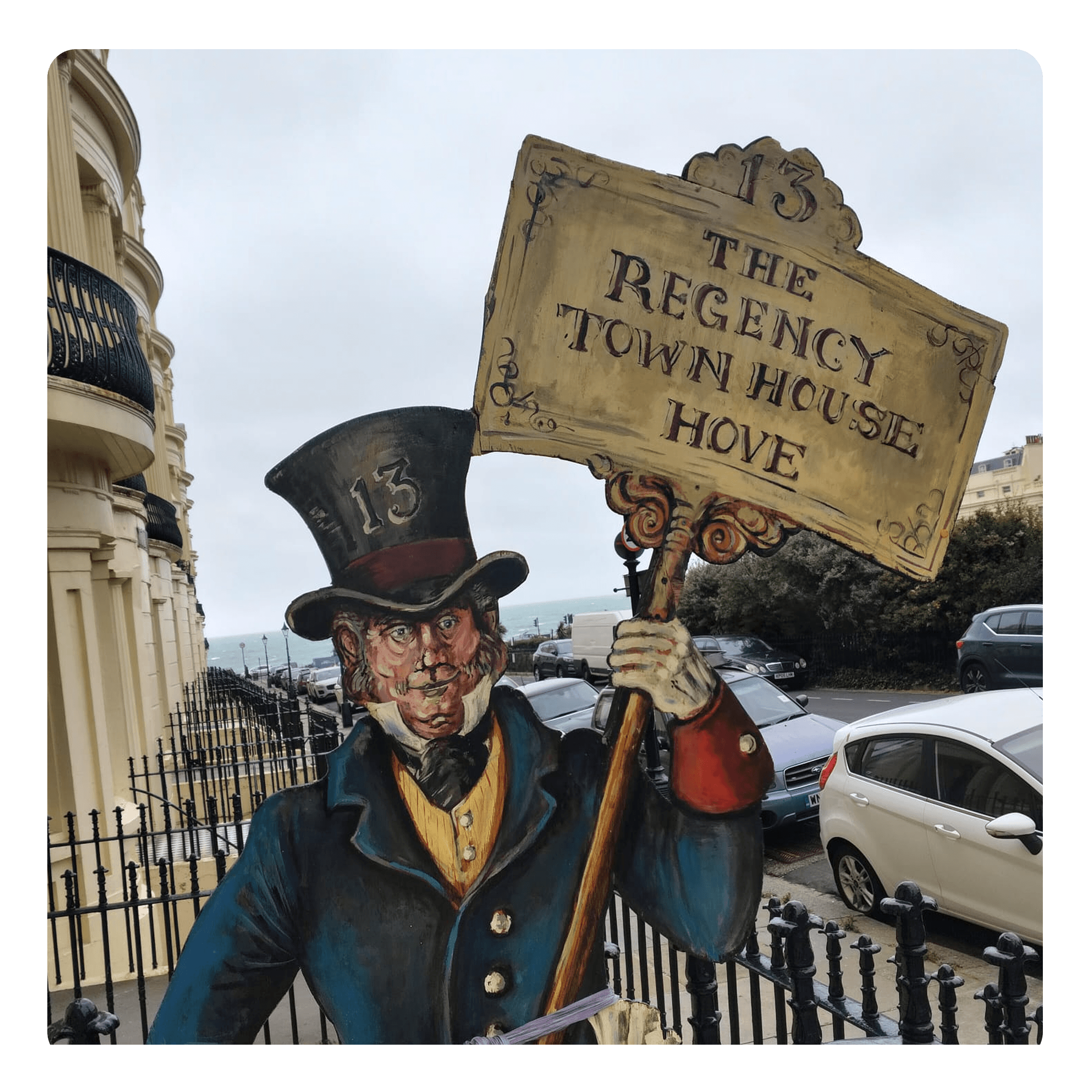

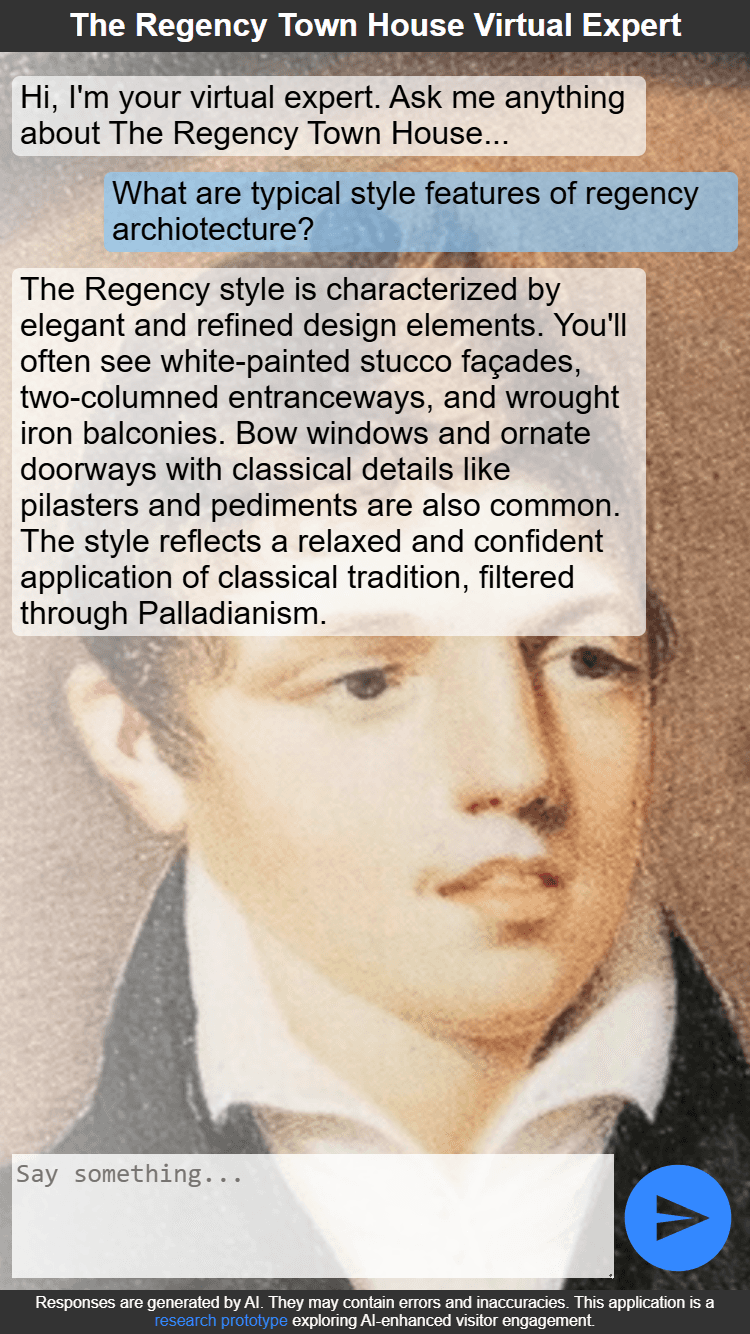

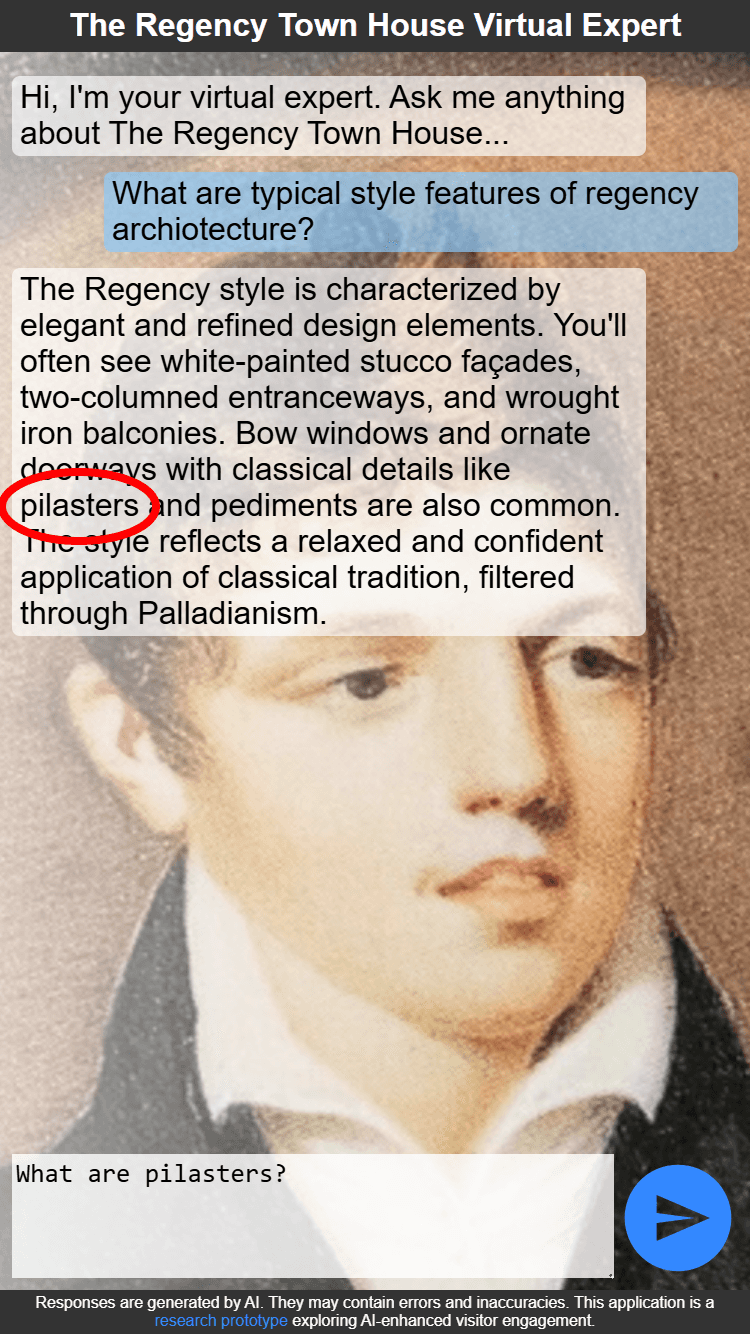

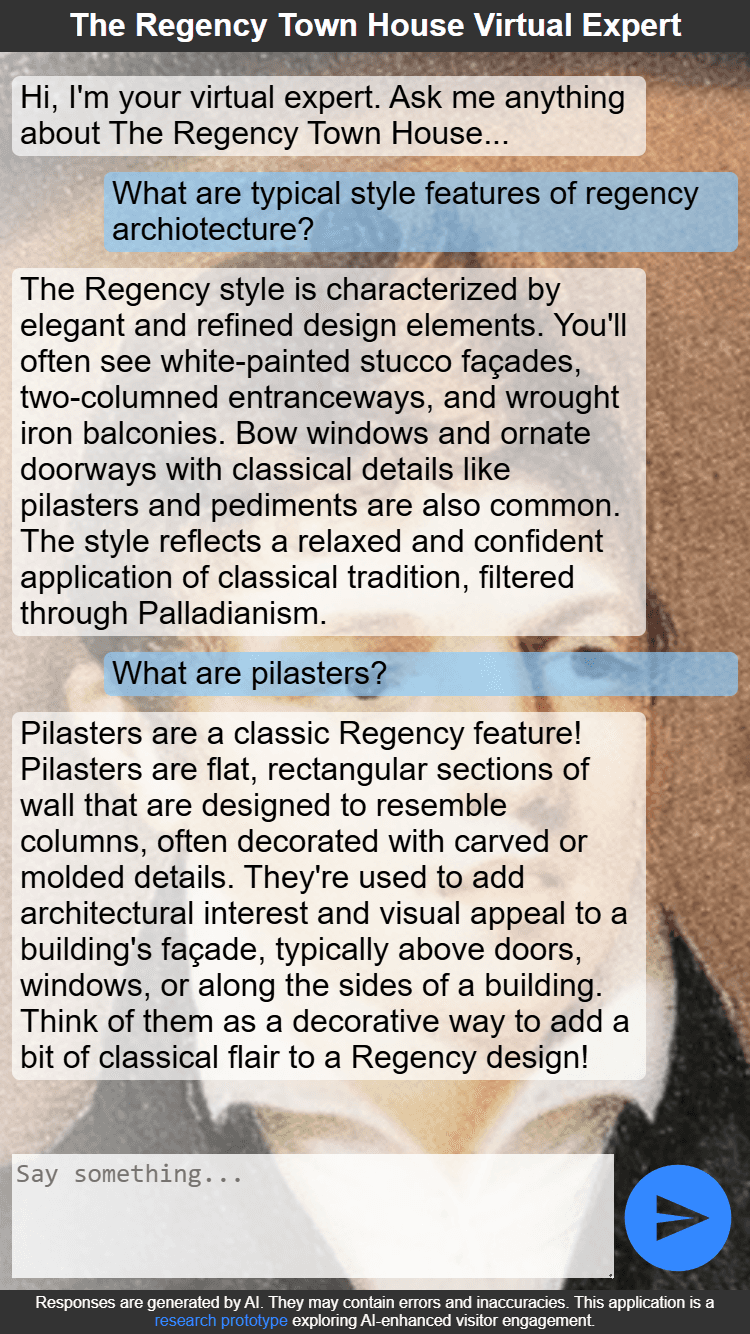

The Regency Town House has rich architectural and social history knowledge, but visitor learning depends on staff availability. A prototype AI chat expert was built to bridge this gap, but key questions remained unanswered: Do visitors want to use AI for expert knowledge? What modality (text vs. voice) feels right in a heritage space? What accuracy threshold matters? How do device and context shape interaction? These insights were needed to validate the concept before further investment.

Task

As a mid-level UX researcher, lead the public evaluation of the Rex prototype. The goal was to understand visitor attitudes toward AI-enhanced learning, gather evidence on modality preferences (text, voice, hybrid), identify usability barriers, and uncover what builds or breaks trust in an AI expert system in a museum context.

Action

Text chat is viable in museum settings: 18/20 visitors found text acceptable; low barrier to adoption compared to voice.

Accuracy is non-negotiable: 13/20 explicitly noted hallucinations or vagueness (especially on materials, room features, historical details). Visitors tolerate a clinical tone if answers are trustworthy; inaccuracy erodes credibility.

Device + modality are context-dependent: Mobile + text dominates (handy, private, portable). Voice interest exists (8 voices) but with conditions: headphones, quiet space, low self-consciousness setting, or specific use cases (accessibility for vision/motor). Not a default.

Self-consciousness & social awareness matter: 7/20 hesitant about voice in public; privacy and "feeling stupid" asking a bot are real barriers. Text avoids social friction.

Scaffolding lowers friction: 3/20 struggled to start conversation. Suggested prompts ("Ask about the fireplace," "What was this room used for?") removed blank-page anxiety.

Trust requires hybrid: Visitors want AI as backup, not replacement. 11/20 expressed preference for human expert with AI as option. Transparency ("this is a prototype, may have errors") was valued; deeper privacy/ethical disclaimers were seen as overload.

Study Design:

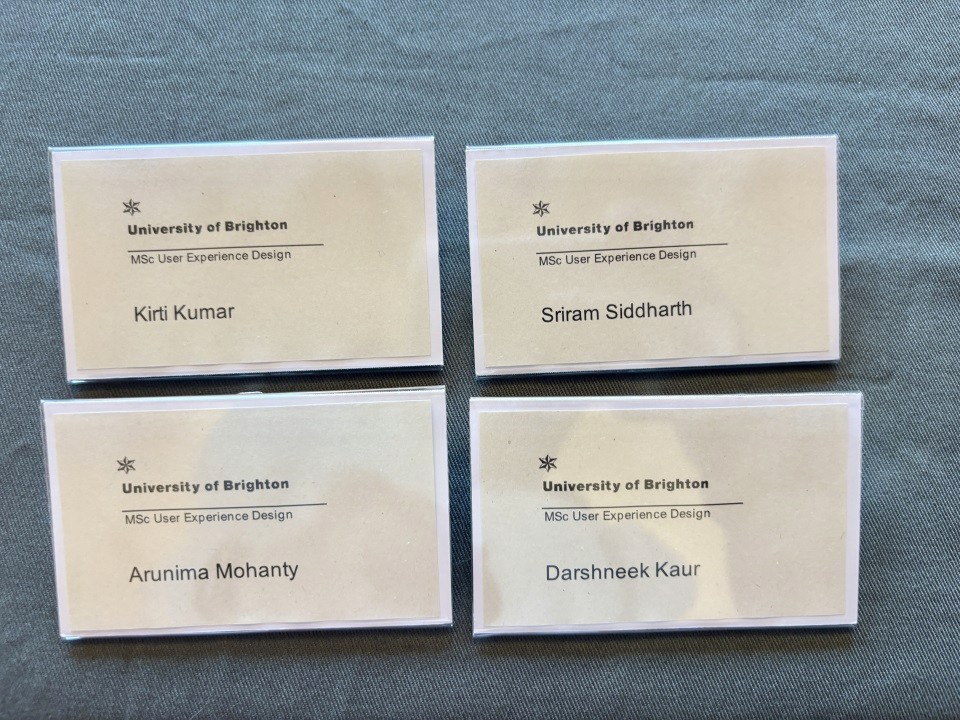

Recruited 20 diverse visitors (mix of Town House first-timers and repeat visitors) via newsletter, radio, and university channels.

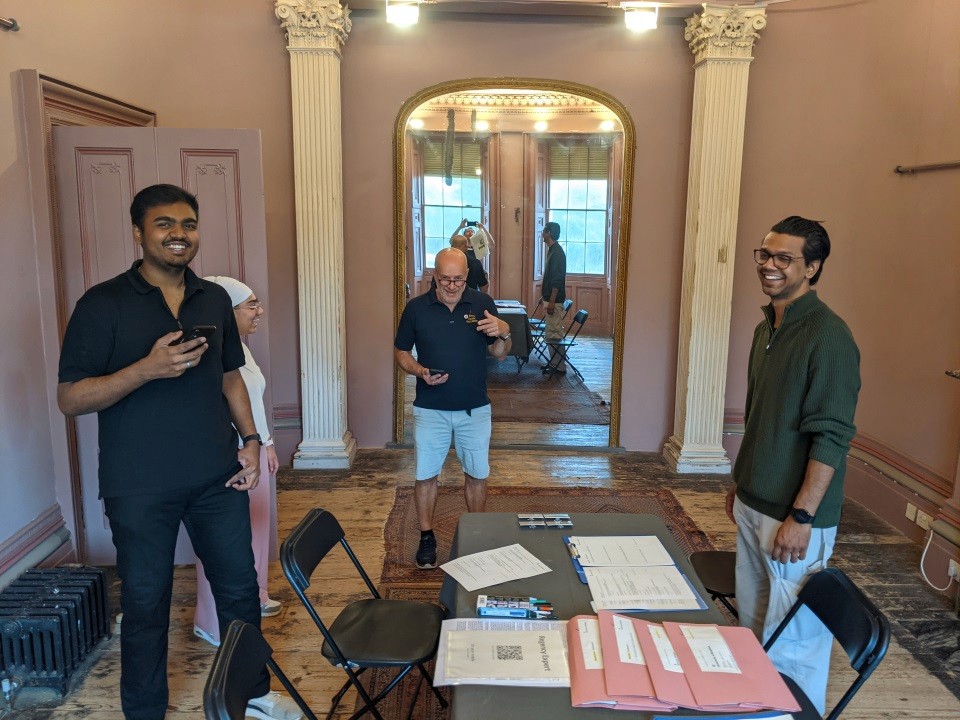

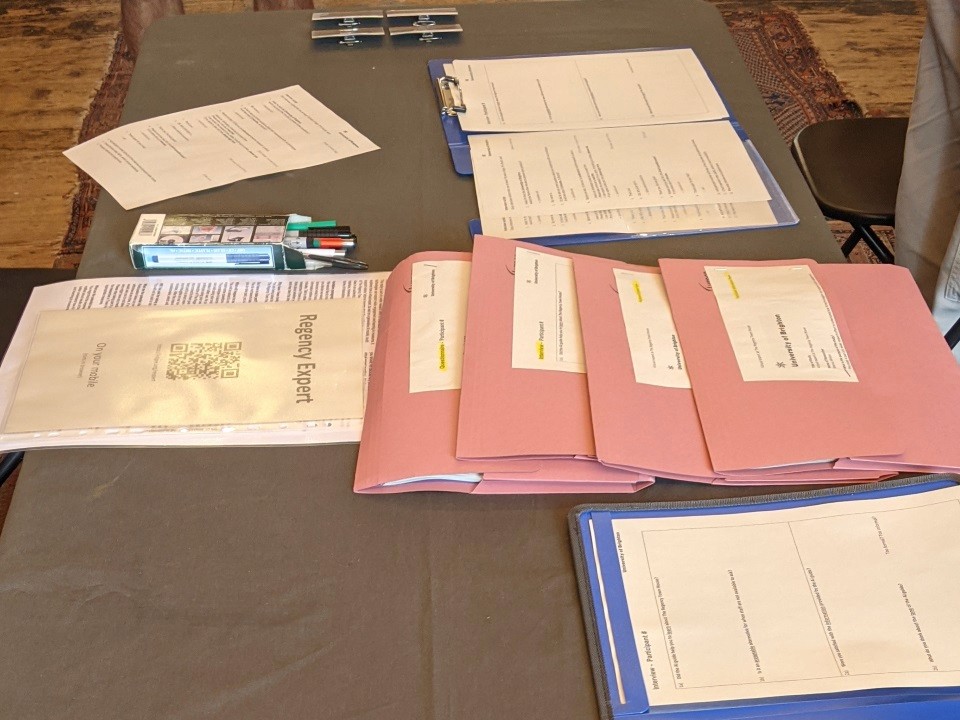

Structured observation: visitors explored the drawing room freely and asked the AI expert natural questions; one researcher observed without intervening.

Post-visit semi-structured interviews (20–30 min each) with open-ended and targeted questions on: engagement, accuracy perception, tone, device preference, text vs. voice comfort, and willingness to use AI as staff alternative.

Distributed questionnaires capturing demographics, prior AI experience, and baseline expectations.

Data Analysis:

Coded all 20 interview transcripts for themes using affinity mapping: grouped responses by topic (accuracy, modality, usability, trust, device context).

Quantified preferences: tallied device choice, voice/text preference, accuracy concerns, self-consciousness triggers.

Synthesised patterns: identified which visitor segments (age, comfort with tech, familiarity with venue) shaped interaction choices.

The research revealed that accuracy and trust are primary, modality is secondary. A perfectly polished voice interaction loses credibility with one hallucination, while a clunky text chat builds confidence if answers check out. Also, museum visitors don't need conversational warmth—they need reliable facts. The biggest insight: visitors aren't rejecting AI; they're rejecting uncertainty. Investing in knowledge base quality and explicit error indicators matters far more than interface polish. This shifted the team's roadmap from "add voice interaction" to "deepen domain expertise and reduce hallucinations" for the next phase.

Results